The Twelve Secrets of the Woods: a Woodcraft Girl knows them and other beautiful and wise things: by Ernest Thompson Seton, founder and chief of the Woodcraft League

Do you know the “Twelve Secrets of the Woods?” Not just any twelve wonderful things that you may have discovered in the woods, but the twelve great secrets that all the Woodcraft Girls know, that make them intimate with Nature, that they have discovered camping out deep in the woods or close to the edge of a stream or in the trails leading up some rich, green hillside. There are always wonderful mysteries to be discovered by everyone who knows the trail to the heart of Nature, but these especial twelve secrets are practical as well as mysterious, and are really part of the equipment of every nature lover and every girl who knows anything of outdoor life — that is, who has lived out of doors as the Indians used to live, taken care of herself, fed herself, made her own bed, built her own fire, watched the dawn come through the trees and slept soundly through wind and rain.

I am not going to answer all the questions involved in these twelve secrets, because if you are really interested in them you will join the Woodcraft League and learn them by heart as well as many other beautiful and wise things. But I am going to ask you a Woodcraft secret and see if you can answer it for yourself, and if you can, you are by instinct one of us, and if you cannot, I think you will feel a little sad. “Have you proved the balsam fir in all its fourfold gifts — as a Christmas tree, as a healing balm, as a consecrated bed, as a wood of friction fire?” If you do not know the balsam fir in these four relationships you have missed one of the great gifts that nature holds for you. One of the twelve secrets is this knowledge of the fir, the right use of the fir for your own happiness.

If you have ever walked down a shady pathway of an autumn day or over a hillside shaded by chestnuts or butternuts, you have seen nimble little squirrels rushing along fences, waving to you from high branches, and you may have stopped to watch them bury every other nut. Have you asked yourself why this is done? If you have an answer, then you know one of the twelve secrets.

And if you have ever wandered far enough from your city home in the East or the West to discover the “manna food” that grows on rocks summer and winter, and holds up its hands in the Indian sign of innocence, proclaiming its goodness to the world, then you know another secret, a secret that might save your life if you chance to be lost in the woods or on the prairie or along the seashore.

To know all these twelve secrets is to be more or less self-reliant and self-contained as a human being. You may not need them on Broadway, although they would add to your happiness there because you would feel richer than most people you meet; but if you are determined to have real life as well as cosmopolitan life, then they must be a part of your educational equipment, a very important part, but really just the beginning of it. The Woodcraft League is really a new kind of education for the American girl; it is a fine democratic sort of education, because it is equally important for every girl from every walk of life. There is no girl who wants a really happy, useful life who can afford not to have this education. and the life of every girl, whatever her occupation in life, will be the richer for it. Also, I firmly believe that it will bring together young people from various so-called stations, break down the barriers that society has foolishly placed between them, and establish in their minds while they are young a finer kind of humanity, a real understanding that the important thing is the association of the human spirit, the organization of human beings set apart with conventional barriers. There is no way of so widely separating people as by a variation of education, and although America is a democratic nation and the high school system is supposed to break down social barriers, as a matter of fact we do not accomplish much in the way of democratic education through the schools, because the people who most need simple, general instruction are not sent to the public schools, but to special educational organizations where they gain much that is beautiful but not the kind of human intercourse which would be so valuable.

If you are a Woodcraft Girl you are bound to learn so many kinds of useful things and you are associated with so many kinds of girls who know these sane, beautiful and useful things that you feel at once a deep and wide human comradeship that can only exist, it seems to me, when based upon fundamental intimacy with Nature’s ways — the only unchangeable inevitable ways. And if the young people of this nation can be so trained that they will grow to look upon Nature with eager interest, if they become familiar with her traditions, her kindness, her discipline, her beauty, her tragedies, they will find themselves held together by a bond of sympathy that no superficial, social structure can ever obliterate.

We have various laws, various regulations, many departments in the Woodcraft League and all the work that is done by the girls is progressive. You graduate, as it were, from one rank to another, and you graduate not merely by what you learn, but by what you do with what you learn. You not only must know Nature intimately; but you must know how to live with her in a peaceful, comfortable way; and when you have learned how to live with Nature you will find that you are a very well educated girl along practical, wholesome, democratic lines. You will also learn very much in the way of fine character building, such things as reticence, courage, unselfishness, obedience, respect for wild life, the sacredness of truth, deference, interest in work, and, perhaps most of all, the joy of being alive, because these things which should be fundamental in every life are fundamental in the Woodcraft life.

There are Twelve Laws for the Regulation of Life for the girls who join the Woodcraft League, just as there are the Twelve Secrets of the Woods to stimulate and illumine the mind. At the very start, you are taught to be brave, rather you want to be brave because you are enabled to see how fine and necessary it is; you are taught the value of silence, of cleanliness, not only personal, but the need of a clean environment for yourself and your spirit; you are taught not only to love the woods, but to preserve the woods; you learn to respect all worship, and then in addition you must be kind and you want to be; there is no other spirit among the Woodcraft Girls, just as there is no other spirit except to be helpful. And, strangely enough, you are also taught the value of good nature. You realize after a very short time among your Woodcraft friends that it is better for your spirit, for your health, for your achievement to be amiable, whether you are sick or well, whether you are in the midst of comfort or discomfort. And in a very short time you learn also that work is a very good thing because it helps to make you and your friends happier and more comfortable.

If you happen to be a young girl well taken are of in a city home, you can be made very comfortable without doing anything for yourself or for anyone else; but if you are a Woodcraft Girl living in the woods you cannot be comfortable for a single minute if you have not worked and planned for your own comfort as well as for others. In other words, I am striving to make it clear that in all the work and study of the League you are not entitled to comfort or happiness unless you have given the equivalent, unless you have earned it, that every person must pay their way in life for everything they have. Grown people learn this soon enough, but the cared-for young people are sometimes not allowed to learn it by the thoughtlessly affectionate parents who do not realize that youth is robbed of its equipment for life if it is not taught that it has no right to anything in the world that it does not in some way earn.

At the very beginning of the work of the Woodcraft League the girl is started on what is called the “initiation trail”, and wonderful things are learned along this pathway — the beauty of that most marvelous and almost unknown things to youth — silence, and after that, usefulness, making her own bed, her own lamp, her own fire sticks, a basket in which she may gather firewood or carry her clothes to the river's edge to wash. Then the sleeping out of doors without a roof, and, strangely enough, for once at least, fasting twenty-four hours. It is extraordinary how these things that seem so simple to write of enlarge the capacity for thought, increase the imagination and extend the sympathies — three conditions which we do not take into consideration in the ordinary course of education either in our schools or our universities.

We seek thus first of all to refresh the spirit of youth, through a close association with Nature and a careful study of her ways, and then to develop the qualities that bring about a real comradeship. The more material lessons are left until a little later, until the mind and spirit have been so opened that these concrete lessons are not only more easily absorbed, but more eagerly sought.

You enter the Big Lodge as a Wayseeker, then, having learned the rudiments of camp life and begun to understand the charm of the woods, you become a “Pathfinder”. Before one can become a Pathfinder there are fifteen out of twenty-three tests which must be taken satisfactorily. If you know all of these twenty-three tests, rather, if you have ever striven to pass them, I am sure you will never hear again the word Pathfinder without wanting to lift your hat to the Woodcraft Girl who has that honor. Again each test of itself seems a simple thing and yet I wonder how many grown-up people could successfully pass fifteen of them. The very first thing is that you must be able to walk six miles in two hours and write a satisfactory account of what you have seen. You may have graduated from Harvard and Oxford without being able to do this. And I am sure the highest success that a university could shower upon you would not teach you the real importance of the fourth test — to tie a slip knot, a double knot, a running noose, a halter, a square timber hitch, bow line and hard loop; but these are self-helpful things to know if you intend to consort much with Nature.

And can you, for instance, light ten successive camp fires with exactly ten matches, using only wildwood materials? And do you know twenty forest trees, the fruit, the leaf, the trunk and the qualities of the woods, so that the tree becomes to you not merely a tree of some sort or another, but a fellow creature with a name, a personality and a life struggle of its own? Do you know or do you know anyone who knows five edible wild plants? Or take the fourteenth test — have you slept out of doors thirty nights, or, what is far more difficult, have you cooked nine digestible meals by a camp fire for not less than five comrades? Have you taught anyone to swim, or would you know how to take care of anyone suddenly ill or hurt in the woods? Well, if you know any fifteen of these things, and want to be a Pathfinder and are young enough to know the value of real life and real education and real comradeship, you could pass and take rank in the Council of the Woodcraft League.

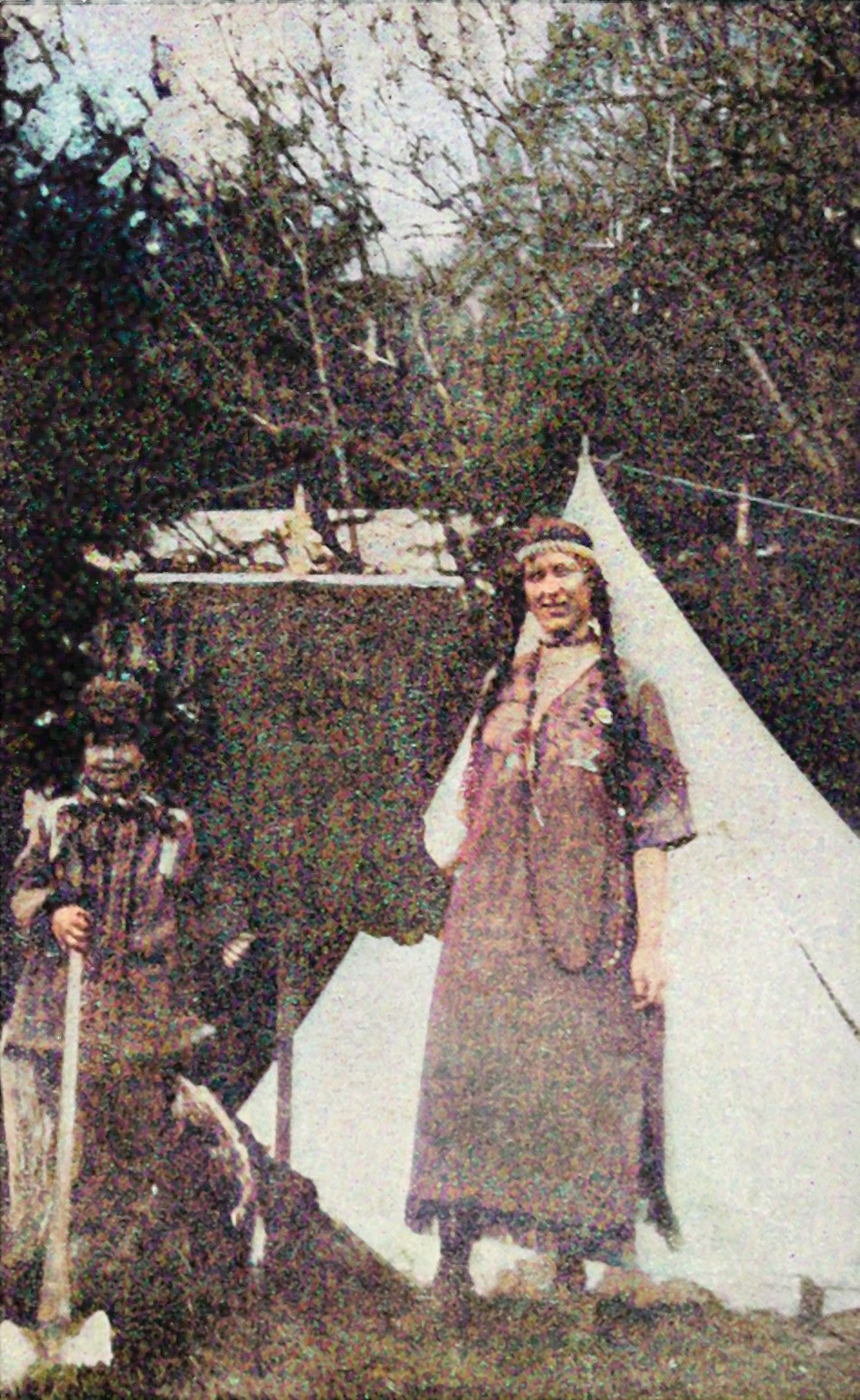

If you are a true Woodcraft Girl it is not enough to remain a Pathfinder; there are many more things to be accomplished, many more honors to be won. You are bound to want to become a Winyan, “a woman tried and proven.” The tests to become a Winyan are twenty-six and twenty of these must be taken. If you can take twenty of them you have a general education of which any girl or young woman would be proud, and which in some phase of life as long as you live you are going to find most useful, not counting the character development you have received in having learned how to do the practical, reasonable things involved in passing the tests. You will have to know twenty wild flowers and five medicinal herbs: you will have to know how to make a comfortable rain-proof shelter of wildwood material. This, of course, will never be needed of Fifth Avenue but the power to master your surroundings that it gives you will be needed at every turn throughout your life. Such power is also fostered by your knowing how to set up your tepee single-handed; by being able to swim one hundred yards in three minutes; the last a not to be despised accomplishment in these days of the undisciplined U-boat — and a hundred other specified activities in the Birch Bark Roll or Manual.

Think of knowing that you have planted ten desirable trees and ten wild flower roots, that you have cleaned up at least one block in your own town, that you have successfully managed an outdoor camp for at least a week; and here is an extraordinary test that you must pass before you are really a “woman tried and proven.” All in one test you must know the methods for panic prevention, what to do in case of fire, electric, ice or gas accident, how to help in the use of a runaway horse, a mad dog or a snake bite, what to do for earache, toothache, grit in the eye and many other difficult situations which fifty per cent, of the grown-up men and women are panic-stricken in the face of.

There are many more departments than just these spiritual and practical ones. For instance, you must learn how to organize tribes, you must learn how to become a ruler of a tribe, you must learn how to bring in and train new members. And then there are special departments for the better understanding of life, for enlarging of your opportunities for making good, for becoming useful members of society. There is one called “The Hunter in Town”, which demands that you shall do many things in the way of civic improvements. Then there is the Needle-Woman branch, and there are thirty-eight tests before you are acknowledged a prize needle-woman. I do not know a single girl or young woman who has had the usual school education who could pass these tests, and I do not believe that one out of the thirty eight is without its actual value for the development and usefulness of woman-kind.

And when you have become a needle-woman of fame, you may also take the degree of the canner and jelly maker. This is a delightful department. It reminds one of the education the pioneer women of America must have had and must have given their daughters, and it certainly would add to the popularity of any young woman to be able to do all that is demanded of her as a real jelly maker. But it is not enough to be a needle-woman and a jelly maker; you may, if you wish, become a housekeeper in the highest sense of the word, that is, one possessing all the knowledge for the comfort of real home making, by entering the lists of the Colonial Housekeeper. The tests here are twenty-nine and they involve the learning of many of the most delightful occupations, it seems to me that youth could turn to. Fancy gathering bayberries and making a half dozen candles; gathering the sap and making a pound of maple sugar; dyeing pieces of dress goods and skeins of yarn; or dyeing twelve squares of felt in different colors with stuffs found in the woods — butternut bark, golden oak, sassafras, golden rod tops! It is a pastime for a Shakespeare sonnet. Also you must know how to make a cherry balm of black cherry bark, and you must crochet your own sweater and you must gather the hops and make a hop pillow and you must know how to make candied fruit and mincemeat and you must brew sage tea and cammomile tea for the health of your playmates or, happily some day, your family. And you are taught to candy sweet flag and mint leaves and you make a marigold salve, which sounds like some mysterious fairy ointment, and then after you have become a Colonial Housekeeper, there are still more honors, a greater knowledge of Nature, a wider understanding of humanity that await you.

All human beings delight in badges that are the outward visible symbol of some inner excellence, the proof of prowess, the evidence of achievement. So for each of these ranks, degrees and exploits, we have provided a suitable badge. The newcomer is entered as a Wayseeker and receives the badge of the order, but on it are two tassels of green, the proof of verdancy. One of them is cut off at each successive stage, and the Winyan wears the badge unsullied by any such derogatory emblems.

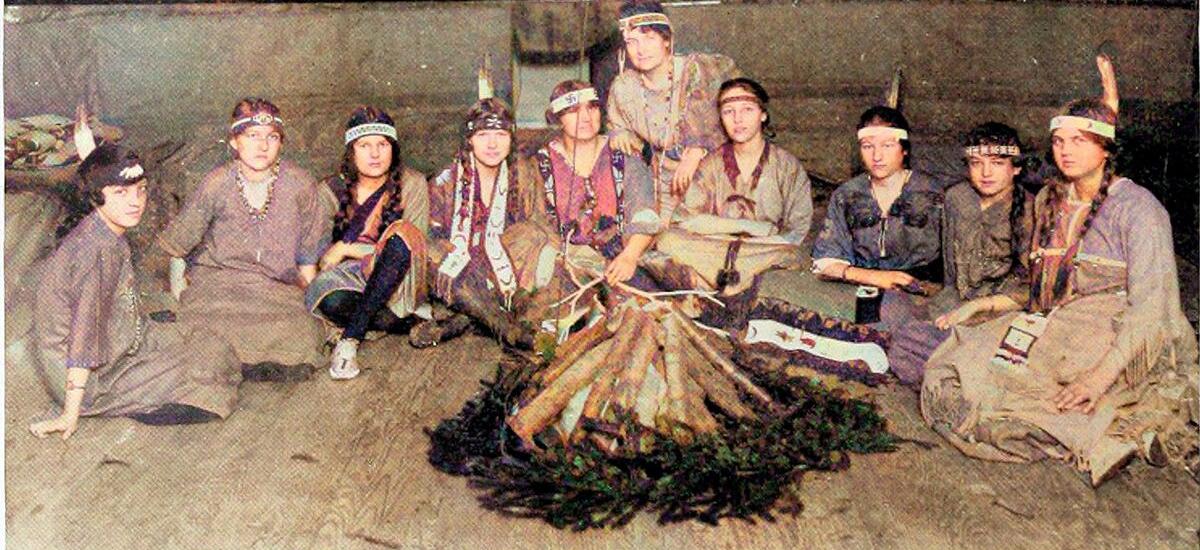

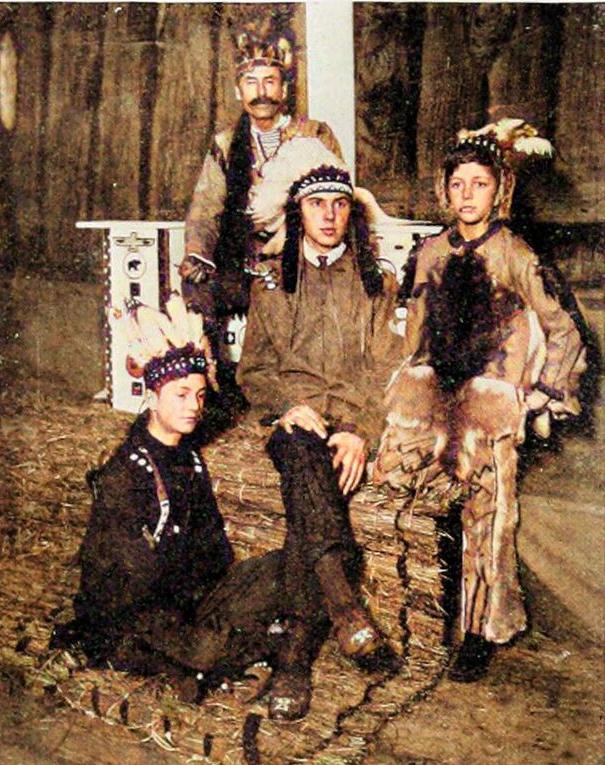

By the number of feathers these boys wear we judge they have many honors.

A Council robe is supposed tu be a possesion of every member. It may be of any material dictated by individual taste, but the badges on it are the same for all. Every exploit and degree has a proper place for its display on the council robe as well as on the person of the winner.

Do you not see now, my old friends and my young friends, the power for the building of a richer and truer democracy that lies in the education of the Woodcraft Girls? We do not argue, we who have the progress and the spread of this education so deeply at heart, that it obviates the need of other education, but we do believe that if only one education can be obtained, none could be more practicable and desirable than this, and that as a supplementary course in pure democracy (for nature is the instigation of all great democracy), nothing more genuine, more enlightening has as yet been devised. It does not take young people away from their daily duties, from their home life, from their regular education, but adds to those duties the glorifying touch of romance, the sense of form, and whether in town or country, work or vacation offers to all the sweetest of all joys, the seuse of some little triumph every day.

One of the great faults of our educational systems today is that education which is called “work” and play which is separated from work, have no relation to each other in the lives of our young people; whereas all education should be the enlarging of the faculties which make for apprecation of play, and all play should be associated with a mental and spiritual development which must bring about a better capacity for work. In other words, everything that develops the youth is interrelated in life, and a work that is not joy and a play that is not productive are equally deleterious. There is very little idleness in the Woodcraft life of our outdoor girls; but I do not believe that after a few weeks or months of this camp life that any one of the girls who have commenced to work and study with us have ever felt for an instant that they were not having adequate enjoyment, that their vacation was not bringing them all or more than ever before.

Of course, I realize that a numher of these tests which the Woodcraft Girls pass as they move on from one achievement to another will be regarded as unimportant or as superfluous and possibly no one is absolutely essential, for what we are seeking is not to teach facts, not to cram more statements into the weary storehouse of youth's brain, but to enrich the imagination, to set a higher standard on pure enjoyment, to bring an understanding of the real humanities into the life of youth; in other words, to form the character of our young people, to do it unconsciously so far as the young people are concerned, and instead of preaching or moralizing or punishing, to so open the minds and hearts of the American youth that the real things of life will be sought after eagerly and become so fundamental in the character that life itself must inevitably be molded along richer lines, touch higher ideals. I do not believe that you can mold character through words; it must be done through deeds, and constructive development of the youth of America seems to me rather more important than the reformation of the youth because of lack of constructive training. A wise general does not attack Gibraltar in front, but from the side or rear. The indirect attack is usually strongest. So also we say little about our national failings, but offer alluring activities that shall ultimately rout these failings out, for illustration — we are wasteful, we have been shockingly wasteful of nature's bounties. There is the other thought taking possession.

A little girl with her father was feeding nuts to a squirrel in Central Park. The squirrel had stuffed himself inside and now was burying the rest of the nuts, one by one. The father explained to the child that most forest trees that bore nuts were planted in this way by squirrels, because those nuts that merely fall on the ground were devoured by deer, etc., or were dried up.

“How many nuts that are planted actually grow into a tree, Daddy?" asked the girl.

“Oh, maybe one in twenty.”

“Well, if I gave that squirrel sixty nuts that it planted would that be the same as if I had planted three forest trees?”

“Why, my child?.”

“Because I want to qualify in the Brownie Lodge. I have got to plant three forest trees for one of the main things.”

The honors of the Woodcraft league are for beauty, truth, fortitude and love, and the smaller vices of childhood are so isolated, so lonely, so unproductive in our camp life and town activities that without much notice or much comment they die a natural death. All our work is to reward accomplishment, not to punish viciousness. We do not find that latter necessary. No child is born bad; and they will never become bad if we do not force them to it by foolish methods. Only give them a chance and do it wisely then all will be well. This is the big thought of Woodcraft.

- The Craftsman vol. XXX. June No. 3., zdroj➚