Nature and Human Nature – A Story of the Woodcraft Idea

- První část vyšla krátce na to jako součást 20. vydání Birch Bark Roll.

- Druhá část – vyprávění o vzniku prvního woodcrafterského kmene, je zajímavá mnoha pozoruhodnými detaily, které se v žádné jiné verzi tohoto příběhu neobjevily.

Woodcraft is a man-making scheme with a blue-sky background. Woodcraft is recreation, preferably out of doors. Unlike some other organizations, the Woodcraft League does not deal with vocation, but with avocation. Laundry work, plumbing, school teaching, banking, real estate or insurance are perfectly honorable callings, but woodcraft does not propose to give an honor to the laundress who has ironed 24 collars without singeing them, to the banker who has signed 100 successful bond issues, to the school teacher who has taught 1000 scholars, to the real estate dealer who has sold 100 lots at double profit, to the insurance agent who has taken $100,000 worth of insurance and never landed his company in a loss, or to the plumber who has set 50 toilet sets without a leak. We rather offer to the laundress, the school teacher, the banker, the real estate man, the insurance agent or the plumber, a totally different realm for their thoughts, something into which they enter as a relaxation, something that utilizes their powers of industry and handicraft, but in a wholly different world, a realm of dreams, if you like, an open space where they can forget their laundry work, their plumbing, their banking, etc., and rejoice in the things of the imagination and the beauties of nature.

Let me illustrate in the story of the London shoe clerk. For six days in the week, morning, noon and night, he was engaged in selling shoes. He had no opportunity for recreation excepting on Sundays, when he was too tired to do anything but go, in fair weather, to Battersea Park, and lie upon the grass.

One Sunday morning, a bug came out of the grass and crawled across his hand. He was surprised to see that it was quite beautiful in color — orange with black and white spots.

Next Sunday, he had a similar experience, but this bug was brilliant emerald-green. He had never thought of them as beautiful objects, but this gave him the idea. He looked about for other kinds; after several Sundays, he had at least a dozen — quite different and more or less beautiful. Then he began mounting them on pins, and he looked forward joyfully to a weekly renewal of his bug hunt.

Some friend said: “Why don’t you go to the Library? There are books about these things which tell their names and habits.” But, alas, the Library was not open on Sundays.

Another friend said: “If I were you, I would go to the Museum and ask for Professor Huxley. He is quite sure to help you.”

So the poor, scared little shoe clerk screwed up his courage to call on the famous scientist. Huxley was one of those great men who are always ready to help students and, for the time being, focus all thought on the matter in hand. He received the shoe clerk most kindly, sent to the Library for books, helped him to name his specimens, and told him to come again whenever he needed help.

So this shoe clerk found another field, a new world into which he could enter when free from his shop duties. It infused joy into his otherwise sordid life, and he kept right on till he became the best authority on the insects of the London parks.

Huxley, addressing his class, told them of this young fellow and said: “That is what I wish every one of you to do. Follow your calling, your vocation, with all your energies in business hours, but at other times have some avocation, something that your heart is in, a corner of the realm of the imagination, a big field or a little field, according to your gifts, but one in which you are the best authority, in which you are the king.”

So the woodcraft idea deals not with the shoe clerk in his counter-jumping hours, his vocation, but with his avocation; not with his commercial exploits, but with his Sundays, when he was King of the Bugs of Battersea Park.

The few trades or vocations that are recognized in our official Manual, are part and parcel of outdoor life and camping, or intimately associated with them.

In giving shape to the recreational activities of Woodcraft, the founder has made a lifelong study of human instincts, recognizing: in these age-old, inherited habits of the race, a weapon and a force of invincible power, never forgetting that instincts may go wrong and be a menace; also that to thwart or aim at crushing an instinct is courting disaster.

For example, the instinct to play. This dominates all young animals of high type, and gives, indeed, the training they need for their life work.

Or the gang instinct, which is the real religion of all boys between 8 and 18. At that age, they care little what the teacher or the preacher thinks of them, but they do care what their gang thinks. The hardest punishment any boy can receive is expulsion from the gang. “The fellers won't let me play with them” is the cry of a broken heart. And the crime for which it usually is meted out is “peaching,” that is, treachery to the gang.

Similar power and possibilities are found in the instinct of initiation, the habit of giving nicknames, the love of personal decoration, the propensity to carve one’s name in public places, the craze to make collections of stamps, shells, specimens, etc., the compulsion of atmosphere, the power of little ceremonies, the love of romance, the magic of the camp-fire.

All of these and many more are considered and used in our plan.

One keen observer, noting how completely we utilized the life forces, defined woodcraft as “Lifecraft.” Another, struck by its practicability everywhere, said it was “Where you are, with what you have, right now.” Another said it was “fun for male and female, old and young, with these three underlying rules:

“First, your fun must not be bought with money. Make your fun; woodcraft shows you how.

“Second, your fun must be enjoyed with due decorum. No one must be hurt in body, spirit or pocketbook.

“Third, the best fun is that which appeals to the imagination. Physical fun has its place, but its zest is apt to pass with one’s youth; joy in the realm of the imagination grows with one’s years, and increases with each indulgence in it. At the end of a long life, it means more than at the beginning.”

Now that I have laid such emphasis on recreation, let me justify the same by referring to some well-known facts.

According to many authorities, half our boys go wrong, make a failure of life, are more or less of a burden on society, and in a large and unnecessary proportion, become criminals. Some sociologists have put the number higher than half, some lower. But whatever it may be, there is a vast, deplorable wastage.

Why? Are 50 per cent of the boys born bad? Certainly not! Modern science tells us that about 1 in 2000 is born bad — that is, a pervert, a moron, one destined to be a nuisance, a pathological case that needs hospital treatment really — not jail.

How, then, is it that we have 50 per cent going bad? The answer is simple: wrong methods of upbringing, and especially, wrong methods of amusement.

Over twenty years ago I found myself in the position to realize a dream that most men have held in their hearts. I bought a stretch of wild land in a country place. Considerably over a hundred acres there were, most of it covered with glorious woods, but varied with rocky hills, a beautiful brook and a lake. Around this I put a ten-foot fence, tight for man and beast, and stocked the place with animals and wild fowl. Here I intended to carry on many experiments and live a life that is commonly considered ideal.

I paid for the place and thought I owned it. But the boys of the neighboring village thought otherwise. I had fenced in waste land on which they long had hunted and played. I was an outsider, an interloper, a nuisance, and they set about freezing me out. Their idea of doing the same was by making it hot for me. They destroyed my fence, they painted wicked pictures on my gate, they shot my animals. All summer long the gang kept up this work, and all summer long, thinking I could wear them out with patient nonresistance, I repaired the fence, repainted the gate and replaced the animals, without any prospect of the warfare ending.

One Saturday morning in September I was busy painting out some shocking frescoes on the gate when a gang of these boys came by. I said to them: “Now, boys, I don’t know who has painted this gate, and I don’t wish to know, but if you know, I wish you would ask him to stop. It does not do the gate any good. I simply have to paint it over again, and it already has had as many coats of paint as are of any use.”

The boys said nothing, but giggled, whistled and passed on.

The next morning, the gate and the fence, and even the adjoining trees and rocks were covered with dreadful pictures that not even the Sunday newspapers would have printed, and they were further embellished with inscriptions to give them personal point.

I saw now that talking had no effect. I had already proved pacifism a failure, and I set about a different scheme.

On Monday morning I went to the village school and asked the teacher if I might talk to the boys for five minutes. She said: “Certainly! Go ahead.”

Then I said: “Will all the boys twelve years old and upwards please stand?” They did so. There were about a dozen. I continued: “Now, boys, I invite you here standing, and any that may happen to be away today, to come to my place at the Indian village on the lake next Friday afternoon after school, to camp with me there from Friday afternoon till Monday morning before school. I will have tents, boats, canoes, firewood, grub — everything necessary for a campout. I ask you to bring only two blankets each, and I ask you not to bring any guns, matches, tobacco or whiskey. These things I will not have in camp. Now, will you come?”

The answer was a most eloquent outburst of — dead silence. There was not the faintest sort of response, not a gleam of interest that I could see. I was puzzled. I knew that many of these boys had been in my Indian village — because it was forbidden. They knew all about the location and its possibilities for fun. But not a word did they say in reply to the invitation.

Thinking that they had not understood me, I repeated and said: “Remember, you do not have to pay anything. You come as my guests. We are going to camp out and have some fun together.”

No answer at all from any part of the room was heard. I was facing a stone wall of stolid silence and was wholly at a loss. Had they said no, I was ready to meet it. Or a qualified yes, I could have managed, but blank, expressionless silence was beyond me.

Standing close to me in front was a tall, good-looking boy with very bright eyes. I sized him up as no fool. Addressing him directly and personally, I said: “Don’t you care to come for a camping trip in the woods, with everything provided?” His answer was a nod of the head.

I picked on another fellow farther back, and to the same question I got a similar reply. Assuming that this was what they meant, I left without further questions.

That week, I made complete preparations for the camp. Tents, tepees, boats and canoes were put in good shape. One of my men was appointed cook, and provided with abundance of provisions. I had seen a dozen boys, but to avoid any pinch I prepared food for eighteen. All was ready Friday at four o’clock. But no boys came.

I waited patiently until quarter after four — but no boys. Half past four — and no one. Now, my cook, who did not at all relish his job, began croaking: “I told you! I told you so! You won't get any satisfaction out of them fellers. The only thing that will do them any good is a rawhide, well laid on the right place.”

I said: “No, I don’t believe in that. I have seen it tried many times, and I have never seen it work.” But I must say I felt very unhappy.

Ten minutes later, and my nervous worry increased. I had nothing to do but wait. I could not help thinking of the old nursery rhyme: “Mr. Smarty gave a party and nobody came.”

My cook’s croakings grew jubilant; but a quarter before five (sunset 18:07) there was a racket and a riot on the main drive, and in came the boys all together. Not the twelve I had seen, not the eighteen I had provided for, but — forty-two, a perfectly ideal party — twelve invitations and forty-two acceptances.

In they came, each carrying his two old blankets. They got over their bashfulness in about ten seconds. Then one of them said: “Say, mister, kin we holler?”

“Surely,” I replied, “blow your lungs out if you want to.” And they tried. The neighbors told me afterwards that they heard them two miles away. I quite believe it.

Next they asked: “Kin we take off our clothes?”

“Yes, indeed,” I answered, “every rag, and the sooner the better.” So the gang peeled off and jumped into the lake. And very glad I was to see them there. Tearing through the dry woods, I did not know what mischief they might do. But in the lake, I could watch them and keep them out of harm. They swam and splashed and pelted each other with mud, and upset the boats for about an hour. Then we called them to supper.

They came, and in the language of Scripture, “they did eat.”

I never saw boys eat harder or more. All the food provided to last till Monday, they cleared up that night. Which was all right, their number being unexpected, and Saturday next day gave a chance to restock. After stuffing themselves for an hour, they were lying around, limp with feeding, like a lot of gorged boa-constrictors.

Then I gathered them around the blazing fire and played my next card. I said: “Now, shall I tell you a story?” The leader shouted: “Ye betcher life! Go ahead!’” Thus graciously permitted, I went ahead and told them stories of wild life and animals I had seen, carefully working up to a grand climax. About eight o’clock, as I looked around the group with the black forest behind and the stars overhead, I noted that the little fellows were not at all sleepy, and the big fellows had ceased their rough, practical jokes. All were listening.

Then I decided that the psychological moment had arrived for my next move. I said: “Now, fellows, how shall we do this campout? Any old rough-and-tumble way, or in the real old Indian fashion?”

In view of the atmosphere which I had deliberately created, there was only one answer possible. They shouted: “Injuns, ye betcher life!”

“Very good,” I replied, “that will suit me. Now this is the tribe. Each brave has one vote, and we begin by electing a head chief.”

Then these boys gave their very first symptom of politeness. They said: “Guess we’ll take you.” But I promptly crushed their politeness. I said: “Oh, no, you don’t. I am not the chief. I am the medicine man, and shall keep out of sight. For chief, I want one of you — one of the gang.”

Then there were forty-two applicants for the job. Each one had most conclusive reasons why he was the only possible choice. They made an uproar with their disputing, till I said: “Shut up! You are not a lot of old squaws. You talk too much. We'll settle this another way. What fellow here can lick all the others?”

This evoked a howl of protest. “Ah, that ain’t fair. That’s Harry Fitch. He’s older and bigger and stronger.”

“Well,” I said, “if Fitch can lick everyone here, I guess he is the one for chief. But maybe there is some fellow who thinks he can lick Fitch.”

Up jumped Jim Butler. He was perfectly willing to take a chance on it and said he could lick Fitch. I said: “Good! Glad to know where you live. We won't try it now, but we may have to do it some other time.”

Then I put these two up for popular election. The result was an overwhelming majority for Fitch. He was undoubtedly their leader — a big, strong, bold, audacious, courageous, athletic boy of fifteen, but stronger than some grown men, full of life and energy, a veritable dare-devil. All the neighbors said he was within measurable distance of the penitentiary with his endless wild pranks.

I was afraid of that boy. I knew that his influence was very bad and his character was strong. He was the leader of the gang, by virtue of his divine right and his equally celestial left. He, indeed, it was who painted my gate, but I did not bring up that subject.

When I found that the boys were bound to have him as the chief, I got him off as soon as possible by himself and talked to him. I said: “Now, see here, Harry. These boys have elected you chief of this tribe. That is not simply for today and tomorrow and the next day. We are going to keep this going as long as the fellows take any interest in it. That means that you are going to lead all those little kids. Now, I hope you are too much of a man to get them into serious trouble. Just realize that you are their leader.”

He protested in boy fashion that he “wouldn't do nuthin’ wrong. He wouldn’t do anything bad.” Which might mean anything or nothing. I found out later from his mother that it meant a great deal, because it was the first time he had been treated as a person of importance and distinction, and the taste of it was good — it was tonic — it braced him up to meet the responsibility and proved a turning point in his life. That, however, came out long afterwards.

Now, we got Butler in as second chief, then picked a third chief and eight councillors, and I got myself in as medicine man.

Then I proceeded to play Moses. I gave them our ten commandments. In those ten laws, I set forth the things I wished them to do that were not adequately covered by the law of the land.

Which laws with some alterations, continue today as the Law of Woodcraft.

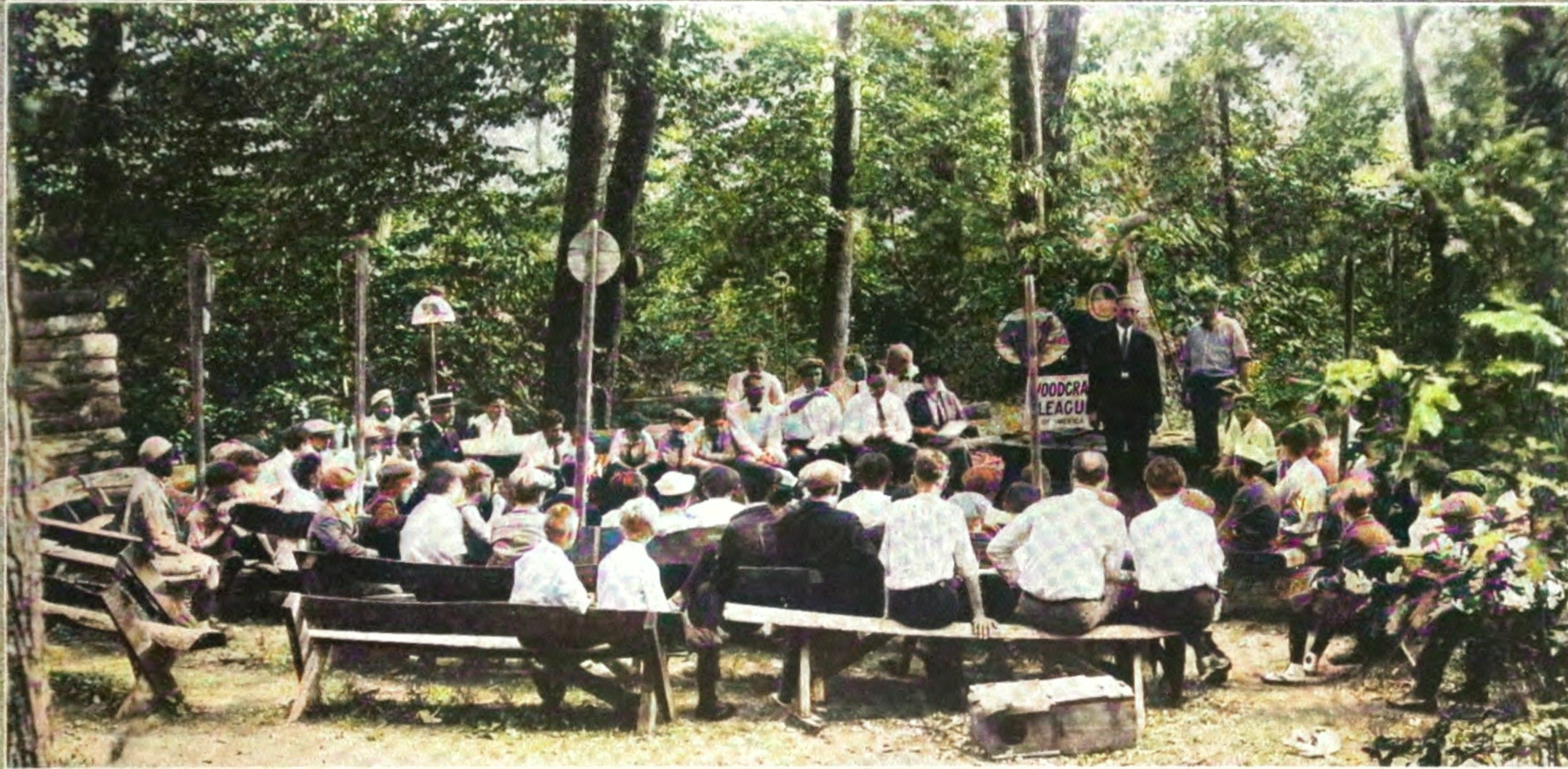

Along these lines, we played the Woodcraft game together till Monday morning came and the boys went back to school, with a wholly reverse attitude towards me. Instead of forty-two little reprobates that the neighbors said were headed for jail, and who were doing all the damage they could to me and mine, I had made forty-two staunch friends, who were bound by and following the Law of Woodcraft. And I have them all today, excepting some who left their bones on the battlefields of France.

Here was a gang of boys getting into serious mischief, solely because they wanted to have some fun. The neighbors called them a bad lot. As it turned out, there was not a bad boy amongst them. The leaders in all their deviltry are fine, outstanding citizens today. Their moving impulse had nothing of the nature of malice, but was simply the exuberant animal desire to frolic. By taking charge of that instinct, I made it a constructive force. Had I taken the other course, one too often followed — that is, called in the police — I should have done more mischief than I could undo in my lifetime. All of those boys continued my active friends. They became my game wardens instead of my poachers. That autumn, a little fellow brought me a cottontail rabbit he had caught, saying shyly: “Say, chief, last summer when I didn’ know you, I shot one of your rabbits through the fence, and I’ve brung this one to take its place.”

That was the founding of the earliest Woodcraft tribe of which I personally was the guide. And in different parts of the country in very different walks of life, I meet its members today. Their ample introduction is: “Say, chief, I was one of your boys.”