How to Play Indian, 1903 (book)

Sešitové vydání, které pod názvem How to Play Indian, 1903 (book) vydalo ho nakladatelství The Curtis Publishing Company – původně mělo jít o dva samostatné “pamflety” z nichž každý měl stát 25 centů[1], jejichž vydání bylo ohlášeno v květnovém čísle magazínu The Ladies’ home journal (1903)[2], v poznámce za pravidelným pokračováním románu Dva divoši. K samotnému vydání došlo pravděpodobně tak, aby ho měli zájemci k dispozici již počátkem července 1903. Obě části nakonec vyšly v jednom sešitu nejspíš proto, že si asi zájemci stejně chtěli nechat poslat obojí najednou.

Protože zde máme k dispozici digitální kopii tohoto vydání[3], můžeme vidět že část o týpí je víceméně shodná s obsahem článku ze září 1902 (viz The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1902 (series)).

Ale organizační část už lze v podstatě považovat za jejich rozšíření. Zde se poprvé hovoří o totemu woodcrafterského národa – bílém bizonu, který byl později transformován do symbolického bílého štítu s modrými rohy – tehdy měl ale ještě podobu stříbrné brože, kterou bylo možné zakoupit spolu s dalšími woodcrafterskými atributy (skalpy) u zásilkového obchodu Abercrombie and Fitch, který tehdy sídlil na Broadwayi v čísle 316 v New Yorku.

Také se zde poprvé uvádí woodcrafterské tituly, ale očíslovaný přehled činů ještě není uveden!

2)

HOW TO PLAY INDIAN

DIRECTIONS FOR ORGANIZING A TRIBE OF BOY INDIANS, MAKING THEIR TEPEES ETC. IN TRUE INDIAN STYLE

BY

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON

Philadelphia

The Curtis Publishing Company

1903

3)

Copyright, 1903, by

The Curtis Publishing Company

4)

TO MAKE A BAND OF INDIANS

Most boys love to play Indian and would like to learn more about doin it. They want to know about all the interesting things the Indians did that are possible for them to do. It adds a great pleasure to the lives of such boys when they know that they can go right out in the holidays and camp in the woods just as the Indians did, and make all their own weapons in Indian style as well as rule themselves after the manner of a band of Redmen.

It is with a view to showing them how to do these things that this little book is written.

Of course there are many bad Indians, and many bad things are done by nearly all Indians, but we wish to imitate the good things of good Indians. Our watchword then is: "The best things of the best Indians," and our object: "The study and pleasures of woodcraft."

First: Get your boys together, and number, from three upward, and organize under leaders as follows:5)

Head War Chiefs elected by the Tribe. He should be a strong boy as well as a popular one, because his duties are to lead and to enforce the laws. He always is head of the council.

Second War Chief, to take the Head Chief's place when he is absent, otherwise he is merely a Councillor.

Third War Chief, for leader when the other two are away.

A Wampum Chief. He has charge of the money and public property of the tribe, except the records; he obeys the Head Chief and Council.

Chief of the Painted Robe, or Feather-tally. He keeps the winter-count and Feather-tally, or book of Tribal records. These rules are pasted in the front of that book. He should be an artist.

Chief of the Council-Fire. His business is to light the council-fire and to see that the camp and woods are kept clean.

Sometimes one Brave holds more than one of these offices.

The Head Chief may add a Chief Medicine Man or Woman to the Council without regard to age, attainments or position. (In one case the Head Chief made his own mother Medicine Woman.) Their duty is to advise the Head Chief.

Add to these all the Redhorns (see p. 11), and elect Councillors enough to raise the number to twenty.6) All are under the Chief. All disputes, etc., are settled by the Chief and Council. They administer the laws and enforce punishments.

VOW OF THE HEAD CHIEF

(To be signed with his name and totem in the tally-book.)

I solemnly promise to maintain the laws and to see fair play in all the doings of the Tribe.

VOW OF EACH BRAVE ON JOINING

(To be signed with the name and totem of each in the tally-book.)

I solemnly promise that I will obey the Chief and Council of my Tribe, and if I fail in my duty I will surrender to them my weapons, and submit without murmuring to their decision.

LAWS

1. Don't rebel. Rebellionagainst any decision of the Council is punishable by expulsion by expulsion. Absolute obedience is always enforced.

2. Don't kindle a wild fire. To start a wild fire — that is, to set the woods or prairies afire — is a dreadful crime against the State, as well as the Tribe. Never leave a fire in camp without some one to watch it.7)

3. Don't harm song-birds. It is forbidden to kill injure or frighten song-birds, or to disturb their nest or eggs, or to molest squirrels.

4. Don't break the Game Laws.

5. Don't cheat. Cheating in the games or records or wearing honors not conferred by the Council is a crime.

6. Don't bring firearms of any kind into camp. Bows and arrows are enough for our purpose.

7. Don't make a dirty camp. Keep the woods clean by burying all garbage.

We do not approve of matches. Two weeks after they have been wholly abolished we allow each member of the Council a grand Eagle feather for maintaining a first-class camp. If all laws have been fully kept and no match struck for two weeks it counts each member of the Tribe and Council a Grand Coup or tufted Eagle feather. The Camp fire is to be made with rubbing sticks.

Punishments are meted out by the Chief and Council after a hearing of the case. They consist of:

Exclusion from the games for a time.

Wearing of black feather for disgrace.

Wearing of white feather for cowardice.

Of tasks of drudgery and camp service.

Of degradation from rank of Councillor or Chief, or reduction in place in Council.

The extreme penalty is banishment from the Tribe.8)

TOTEM

The totem of the whole nation of Seton Indians (as they have called themselves) is the White or Silver Buffalo.

Each Band needs a totem of its own in addition. This is decided by the Council, and should be something easy to draw. Each brave adds a private totem of his own, usually a drawing of his name.

The first of the Seton Indians took as their totem a Blue Buffalo and so became Blue Buffalo Band, and Deerfoot, the Chief, uses the Blue Buffalo totem with his own added underneath.

Any bird, animal, tree or flower will do. It is better if it have some special reason.

One Tribe set out on a long journey to look for a totem. They agreed to take the first living wild thing that they saw and knew the name of. They traveled all one day and saw nothing to suit, but next day in a swamp they startled a BLue Heron. It went off with aharsh cry. So they becamce the "Blue Herons," and adopted as a war cry, the croak of the bird — "Hrrrrr — Blue Heron." Another Band have the Wolf totem.

DECORATIONS

The most important is, of course, the War Bonnect of Eagle feathers. This is a full record of the owner's9)exploits, as well as a grand decoration. It is fully described in "The Ladies' Home Journal" for July, 1902.

Sometimes the Chief wears a single feather, then the rest of the Tribe wear none.

One cannot always wear the war bonnect, yet most want to have a visible record that they can wear. To meet this need we have a silver badge on which one's exploits can be marked. This is adapted from an old Iroquois silver brooch.

The White or Silver Buffalo represents the whole nation. The owner can put his initials on the Buffalo's forehead, if desired.

The pin in the middle is in the real Indian style. To fasten the brooch on you throw back the bin, then work a pucker of the coat through the opening from behind. When it sticks out far enough bend it to one side, pierce it with the bin, then put the pin down and work the puker back smooth. This can never work loose or get lost.

The rank of the wearer is thys shown:

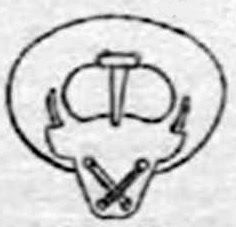

The ordinary brave or squaw as soon as admitted wears the simple badge, so —10)

Every one in the Council is a Councillor Chief, and adds a beard to the Buffalo, using silk through the nostril, of the color he is entitled to. (See later.)

The Medicine Man adds a criss-cross of his color from left eye to right nostril, and right eye to left nostril. Of course if he is on the Council he also adds the beard.

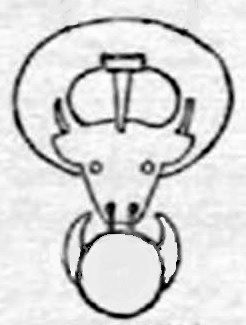

THe Head Chief wears, in addition to the beard, a horned shield. On the circle of the shield is engraved the totem of the Tribe.

The horns are worn only by a Head Chief. The following shows their importance:

"No one wears the headdres surmounted with horns except the dignitaries who are very high in11)authority and whose exceeding valor, worth and power are admitted by all the nations.

"This man (Mah-to-toh-pa) was the only man in the nation who was allowed to wear the horns, and all, I found, looked upon him as the leader who had the power to lead all the warriors in time of war." (Catlin, Vol. 1, p. 103.)

In addition to this, the Grand Coups, or grand tufted Eagle feathers (simple Coups do not count), are marked as follows:

A Brave without Grand Coups (that is, tufted feathers) wears the plain silver badge: if on the Council his Buffalo has a white beard.

A Brave with one to nineteen (inclusive) Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the horns lashed with green silk.

A Brave with twenty to thirty-nine (inclusive) Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the horns lashed with black silk.

A Brave with forty to fifty-nine (inclusive) Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the horns lashed with blue silk.

A Brave with sixty to seventy-nine (inclusive) Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the horns lashed with orange silk.

A Brave with eighty to ninety-nine (inclusive)12)Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the horns lashed with red silk. He is entitled to a seat in Council.

A Brave with one hundred or upward Grand Coups, or tufted feathers, wears the eyes as well as the horns lashed with red silk, has of course, a red beard, and is a Red Buffalo. He is entitled to sit in Council.

Scalps. Each warrior may fasten in his War Bonnet a long tuft of horsehair. This answers as his scalp. He can lose this only in an important competition, approved by the Council, in which he stakes his scalp against that of some other Brave. If he loses he surrenders his tuft to the winner and goes tuftless for one week, during which time he loses his place in the Council.

After a week the Council may restore his seat and give him a new scalp, but the winner keeps the old scalp for a teepee or other decoration, and counts Coup or Grand Coup, as the Council may decide.

Note — These badges and scalps may be bought of Abercrombie & Fitch, No. 316 Broadway, New York. The simple silver badge of a Brave costs fifteen cents. With horned shield for the Chief it costs twenty cents. The lashing is done by each for himself, also the engraving of the totem.

Scalps cost ten cents each, or one dollar a dozen.13)

TEEPEES

Many famous campers have said that the Indian teepee is the best known movable home. It is roomy, self-ventilating, can scarcely blow down, and is the only tent that admits of a fire inside.

Then why is it not everywhere used? Because of the difficulty of the poles. If on the prairie you must carry your poles. If on the prairie you must cut them at each camp.

General Sibley, the famous Indian fighter, invented a teepee with a single pole, and this is still used by our army. But it will not do for us. Its one pole is made in part of iron and is very cumbersome, as well as costly. The "Sibley" is ugly, too, compared with the real teepee, and we are "Playing Injun," not soldier, so we shall stick to the famouse and picturesque old teepee of the real Buffalo Indians.

In the "Buffalo days" this teepee was made of Buffalo skin; now it is made of some sort of canvas or cotton, but it is decorated much in the old style. I tried to get an extra fine one made by the Indians14)especially as a model for our boys, but I found that no easy matter. I could not go among the Red-folk and order it as in a department store.

The making of a teepee was serious business, to be approached in a serious manner. Only an experienced old squaw could do it, and she must deram and think, for perhaps weeks, first; then having worked out a plan in her mind she must call in a dozen of her neighbors to make a "bee" and carry out her exact plan. Any change is "bad medicine" — that is, "unlucky." I waited a year and the tent-making spirit kept away ; none of the squaws felt moved to build a teepee, and I was in a quandary.

One of the Chiefs suggested that if I waited another year I might get one. When the Buffalo came back I should be sure of it.

At length I solved teh difficulty by buying one ready made from Thunder Bull, a Chief of the Cheyennes.15)

It appears in the illustration on page 13, and the working plan of it, laid flat on the ground, is shown in Cut I. This is a 20-foot teepee and is large enough for ten boys to line in. A large one is easier to keep clear of smoke, but most boys will prefer a smaller one, as it is much handeier, cheaper and easier to make. I shall therefore give the working plan of a 10-foot teepee of the simplest form — the raw material of which can be bought new for less than $4.00. This is big enough for three, or perhaps four, boys.

It requires 22 square yards of 6- or 8-ounce duck, heavy unbleached muslin or Canton flannel (the wider the betterm as that saves labor in making up), which costs about $3.00; 100 feet of 3-16-inch clothesline, 25 cents; string for sewing rope ends, etc., 5 cents.

Of course one can often pick up second-hand materials that are quite good and cost next to nothing. An old wagon cover, or two or three old sheets, will make the teepee, and even if they are patched it is all16)17)right, the Indian teepees are often mended where bullets and arrows went through them. Scraps of rope, if not rotted, will work in well enough.

Suppose you have new material to deal with. Get it machine-run together, 20 feet long and 10 feet wide. Lay this down perfectly flat (Cut II). On a peg or nail at A in the middle of the long side put a 10-foot cord loosely, and then with a burnt stick in a loop at the other end draw the half-circle B C D. Now mark out the two little triangles at A. A E is 6 inches, A F and E F each one foot ; the other triangle, A R G, is the same size. Cut the canvas along these dotted lines. From the scraps left over cut two pieces for smoke-flaps, as shown. On the long corner of each (H in No. 1, I in No. 2) a small three-cornered piece is sewed, to make a pocket for the end of the pole.

Now sew the smoke-flaps to the cover so that M L of No. 1 is fitted to P E, and N O of No. 2 to Q G.

Two inches from the edge B P make a double row of holes ; each hole is 1 1/2 inches from its mate, and each pair is 5 inches from the next pair, except at the 2-foot space marked "door," where no holes are needed.

The holes on the other side, Q D, must exactly fit on these.

At A fasten very strongly a 4-foot rope by the middle. Fasten the end of a 10-foot cord to J and18)19)another to K.

Hem a rope all along on the bottom B C D. Cut 12 pieces of rope each about 15 inches long, fasten one very firmly to the canvas at B. another at the point D, and the rest at regular distance; to the hem-rope along the edge between, for peg-loops. The teepee cover is now made. (See Cut III.)

For the door (some never use one) take a limber sampling 3/4-inch thick and 5 1/2 feet long, also one 22 inches long. Bend the long one into a horseshoe and fasten the short one across the ends (A in Cut III ). On this stretch canvas, leaving a flap at the top. in the middle of which two small holes are made (B, Cut III) so as to hang the door on a lacing-pin. Nine of these lacing-pins are needed. They arc of smooth, round, straight hardwood, a foot long and 1/4-inch thick. The way of skewering the two edges together is seen in the Omaha teepee at the end of the line on page 14.

Twelve poles also are needed. They should be as straight and smooth as possible; crooked, rough poles are signs of a bad housekeeper—a squaw is known by her teepee poles. They should be 13 or 14 feet long and about 1 1/2 inches thick at the top. Two are for the smoke-vent; they may be more slender than the others. Last of all, make a dozen stout short pegs about 15 inches long and about 1 1/2 imches thick. Now all the necessary parts of the20)21)teepee are made and it appears as in Cut III. But no real Indian wouldd live in a teepee which was not decorated in some way and it is well to begin the adorning while the cover is flat on the ground. From the centre A at 7 feet distance draw a circle; draw another at 6½ feet, another at 3 feet and another at 2½ feet (Cut IV). Make the lines any color you like, put a row of spots or zigzags in each of the 6 inch bands; then on the side) midway between A and C, draw a 1-foot circle.

In the old days every Indian had a “coat-of-arms” or “totem” and this properly appeared all his tent. This little circle is a good place to paint your totem. The spaces at each cicle can be covered with figures showing the owner's adventures; using flat colors with black outlines, but without shading. Oil colors rubbed on with a stiff brush and little oil are nearest to the old Indian style.

The pictures are usually about the middle of the wall, because when high they get smoked, and when low they get dirty.

In addition to being painted the teepee is usually decorated with Eagle feathers, tufts of horsehair, headwork, etc. In Cut IV the owner's crest, a “Blue Buffalo,” is shown in the small circle, and from that are three tufts for tails. On the teepees on pages 13 and I4 are shown many different styles of decoration22)23)and all of them were from real teepees. Scalp-locks were also used, although horsetails are more often seen now.

When I used to "Play Injun" each of us wore on his head, or at least carried, a tuft of black horsehair which was called a scalp, a.nd when the wearer lost any important competition he gave up his scalp-lock to the winner, who usually thought it looked very well hanging from some part of his teepee. Fortunately after a time of disgrace our Council could always give the loser a new tuft of horsehair.

This is how the Indian test is put up: Tie three poles together at a point about 2 feet higher than the canvas, spread them out in a tripod the right distance apart, then lay the other poles (except three, including the two slender ones) in the angles, their lower ends forming the proper circle. Bind them all where they cross with a rope, letting its end hang down inside for an anchor. Now fasten the two ropes at A to the stout pole left over at a point 10 feet up. Raise this into its place and the teepee cover with it, opposite where the door is to be. Carry the two wings of the tent around till they overlap and fasten together with the lacing-pins. Put the end of a vent-pole in each of the vent-flap pockets, outside of the teepee. Peg down the edges of the canvas at each loop if a storm is coming, otherwise a few will do. Hang the door24)on a convenint lacing-pin. Drive a stout stake inside the teepee, tie the anchor rope to this and the teepee is ready for weather. In the centre dig a hole 18 inches wide and 6 inches deep for the fire.

The fire is the great advantage of the teepee, and the smoke the great disadvantage, but experience will show how to manage this. Keep the smoke-vent swung down wind, or at least quartering down. Sometimes you must leave the door a little open or raise the bottom of the teepee cover a little on the windward side. If this makes too much draft on your back stretch a piece of canvas between two or three of the poles inside the teepee, in front of the opening made and reaching to the ground. This is a lining or dew-cloth. The draft will go up behind this.

By these tricks you can make the vent draw the smoke. But after all, the main thing is to use only the best and dryest of wood. This makes a clear fire. There will always be more or less smoke 7 or 8 feet up, but it worries no one there and it keeps the mosquitoes away. When these pests were very bad I used sometimes to "smudge" my teepee — that is, throw an armful of green leaves or grass on the fire and then run out, close the door and smoke-vent tight, and wait an hour before reentering. These dense smoke would kill or drive out all the mosquitoes in the tent, and the rest of the night there was enough25)of it hanging around the vent to keep the little plagues away till morning.

You should always be ready for a storm over night. You must study the wind continually and be weather-wise — that is, a woodcrafter — if you are to make a success of the teepee.

And remember this : The Indians did not look for hardships. They took care of their health so as to withstand hardship when it came, but they made themselves as comfortable as possible. They never slept on the ground if they could help it. Catlin tells us of the beautful 4-post beds the Mandans used to make in their lodges. The blackfeet make neat beds of willow rods carefully peeled, and the Eastern Indians cut pils of pine and fir branches to keep them off the ground.

Captain W. P. Clark, in his admirable book on "Indian Sign Language," adds these remarks about teepees:

"From fourteen to twenty-six poles are used in a lodge and one or two for the wing-poles on the outside; these latter for adjusting the wings, near the opening at the top of the lodge, for the escape of smoke; the wings are kept at such angles as to produce the best draft. The best poles are made from the slender mountain pine, which grows thickly in the mountains. The squaws cut and trim them,26)and carefully peel off the bark. They are then partially dried or seasoned, and are first pitched for some time without any covering of canvas or skin. By being thus slowly cured they are kept straight. The length depends on the size of the lodge, of course, and varies from sixteen to thirty feet (P. 372.)

"The ground about the fire was overspread with mats, upon which the occupants might sit. Next to the wall was a row of beds, extending entirely around the lodge (except at the entrance), each bed occupying the interval between two posts of the outer circle. The beds were raised a few inches from the ground upon a platform of rods, over which a mat was spread, and upon this the bedding of Buffalo robes and other skins. (P. 374.)

"A cross-piece is tied on to two poles opposite each other, upon which a piece of green wood, crotched at both ends, is forked to hang kettles or pots when cooking; one end of this piece of green wood is forked on the cross-piece, the other holding in these wigwams, and upon which matting is placed, is boughs of balsam, fir or cedar. Hay is also used." (P. 376)27)

Dr. George B. Grinnell, in his "Blackfoot Lodge Tales" (p. 199), says of the Buffalo-skin teepee:

"An average-sized dwelling of this kind contained eighteen skins and was about sixteen feet in diameter. The lowerr edge of the lodge proper was fastened by wooden pegs, to within an inch or two of the ground. Inside, a lining made of brightly painted cow skin, reached from the ground to a height of five or six feet. An air space of the thickness of the lodge poles — two or three inches — was thus left between the lining and the lodge covering, and the cold air, rushing up through it from the outside, made a draft which aided the ears in clearing the lodge of smoke. The door was three or four feet high and was covered by a flap of skin, which hung down on the outside. Thus made, with plenty of Buffalo robes for seats and bedding, and a good stock of firewood, a lodge was very comfortable, even in the coldest weather.

"The owner of the lodge always occupied the seat or couch at the back of the lodge, directly opposite the doorway, the places on his right being occupied by his wives and daughters... The places on his left were reserved for his sons and visitor. When a visitor entered a lodge he was assigned a seat according to his rank — the nearer to the host the greater the honor."28)

Another thing of importance : Catlin says that the real wild Indians were "cleanly." They became "filthy" when half civilized. Cleanliness around the camp should be a law. When I camp, even in the Rockies, I aim to leave the ground as pure as when I came. I always dig a hole, or several if need be, and say: "Now, boys I want all tins, dirt and rubbish put here and buried. I want this place left as clean as we found it." This may be a matter of sentimental in the Western mountains, but in the woods near home you will find you will win many friends if you enforce the Mosaic law of cleanliness, burying all dirt and rubbish in order "that the land be not defiled".

All of the teepees shown on page 13 and 14 were taken from life out West, and they serve o show the great variety of decorations, as well as material. The Catlin teepee was of white leather, the Omaha of unbleached muslin, and the Gray Wolf teepee of red canvas. I came across this last on the Upper Missouri in 1897. It was the most brilliant affair I ever saw on the plains, for on the bright red ground of the canvas were his totems and medicine, in yellow, blue, green and black. The day I sketched it I got a new lesson in the need for watching and knowing the weather if you live in tents.

Gray Wolf had come to camp and I went down to see him and his wonderful teepee. But I happened29)on a wrong time, because that very day a company of United States soldiers under orders had forcibly taken away his two children "to send them to school, according to law"; so Gray Wolf was going off at once, without pitching his tent. He refused to see me or talk to any white man. His little daughter, "The Fawn," looked at me with fear, thinking perhaps I was coming to drag her off to school. I called and coaxed her, then gave her a quarter. She smiled at that, because she knew it would buy sweetmeats at the traders house.

Then I said : "Little Fawn, tell your father that I am his friend and I want to see his great red teepee before I leave the village."

"The Fawn" came back and said: "You must not speak to my father. He hates you."

"Tell your mother that I will pay her if she will put up the red teepee."

"The Fawn" went to her mother, and improving my offer told her that "that white man will give much money to see the red teepee up."

The squaw looked out. I held up a dollar and got only a sour look, but another squaw appeared. After some hagglin they agreed to put up and let me sketch the teepee for $3.00. The poles were already standing. They unrolled the great cloth and deftly put it up in less than 20 minutes, but did not put30)down the another rope, as the ground was too hard to drive a stake into. My sketch was half finished when the elder woman came out of the small teepee near, called the younger and pointed westward over the plain. They chattered together a moment and then proceeded to take down the teepee. I objected. They pointed angrily toward the west and went on. I protested that I had paid for the right of making the sketch and must finish; but in spite of me the younger squaw scrambled like a monkey up the front pole, drew the lacing-pins, and the teepee was down and rolled up in ten minutes.

It was a brilliant and very hot September day.

I could not understand the pointing to the west, but five minutes after the teepee was down a dark spot appeared; this became a cloud and in a short down all teepees that were without the anchor rope, and certainly the red teepee would have been one of those to suffer but for the sight and foresight of the old Indian woman.

Note — Teepees can be bought ready made for $7.00 and upward, of Abercrombie & Fitch, 314-316 Broadway, New York City.31)32)

Numbers 1 and 2 — From Catlin. Colors unknown.

Number 3 — Piegan, from photograph by Mr. E. W. Deming. Ground color, buff, shading above and below dull red; Elk, dull read with white knees, rump, kidney spots and life line (mouth to heart). On the other side this teepee is the same, but the Elk is without horns and faces to meet this.

Number 4 — Sioux. White with all the shaded portion in rather bright red.

Number 5 — Assiniboine. Ground color, buff; top, dull red with row of buff spots, and below these a row of Buffalo tails; the zigzag on each side of the door is red; behind is a brown Buffalo head (Deming).

Number 6 — Piegan. White teepee. Band on side, dull red; above that a row of black Birds; red cross or morning star at top; below that a row of Buffalo tails and a brown Buffalo bead (Deming).

Number 7 — Piegan. General color, buff; band above and band below, dull red with dull blue round spots; Buffalo, slaty with dark spots (Deming),

Number 8 — Blackfoot. Buff; bar near ground, buff and blue with a blue outline, then outside that a bright yellow outline (dots stand for yellow); above are two rows of yellow spots and one row in the middle, of blue; Locks of hair, trimmed with red, hang on the sides and from the smoke-flaps.

Number 9 — Kiowa. From model in the United States National Museum. Buff or gray ground color; the sun at top away from door has dark brown centre a red ring and an outer yellow ring, the rays are red and blue; the top stripe of teepee and bottom are red (marked with upright lines); the lower stripe at the top, the upper one at the bottom and the five-pointed fans above the door are blue. The hair tufts are trimmed with red.

In all of these, unless otherwise specified, the far side is like the front.

These teepees are taken from real ones to show the style, but some Indians are better artists than others and paint better, so that there is great range. We wish to copy the best, and those boys who can draw and paint can make a fine teepee by putting the most careful work into the design and painting. By keeping the design, whatever it is, in the form of rows and processions, and the color flat — that is, without shading — they will not only keep it Indian in charater, but also more artistic and decorative.33)

Here is a fine painted skin teepee of which I got the model from the Sioux. The color are delicate flat tints — no strong colors are used on it. The figures are sharp but have no lines around them. Only pale red, pale yellow and pale green are used. The ground color is soft gray.

RED — All parts marked so: Smoke-flaps and all tops of teepees, stem of pipe, lower half-circle under pipe, middle part of bowl, wound on side of Elk, blood falling and on trail; Horse, middle Buffalo, two middle of two door-hangers, and fringe of totem at top of pathway, and two black lines on doorway.

YELLOW — All parts marked so: Upper half-circle under pipe stem, upper half of each feather on pipe; horseman with bridle, saddle and one hidnfoot of Horse; the largest Buffalo, the outside upright of the pathway; the ground colors of them totem; the spotted crossbars of pathway; the four patches next the ground, the two patches over door, and the rigns of door-hanger.

GREEN — All parts marked so: Bowl of pipe, spot over it; feather tips of same; Elk, first Buffalo, middle line on each side pathway, and around teepee top; two dashed crossbars on totem and dashed crossbars on pathway; bar on which Horse walks; lower edge and line of spots on upper part of door.

- ↑ V ohlášené ceně bylo započítáno nejspíš i poštovné, protože následující knižní vydání z r. 1904 stálo 15 centů a obsahovalo obě části – včetně přehledu orlích per.

- ↑ The Ladies’ home journal. v.20 May 1903 page 12

- ↑ Originál, který pochází z webu http://childlit.unl.edu, nepochybně patřil Setonovi, neboť obsahuje jeho poznámky pro příští vydání!